Quelle: New England Complex Systems Institute

a) A fragile system is damaged — possibly catastrophically,

b) A robust system is largely unaffected, retaining much or all of its prior strength,

c) Some systems actually gain strength, a property which has recently been termed antifragility.

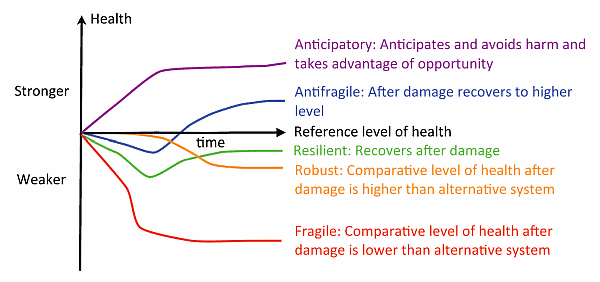

Characterization of the changes in system health when subject to external stresses. System properties can include (a) the ability to anticipate, resulting in avoidance of harm or exploitation of opportunities (anticipatory, purple), (b) the ability to recover from damage to a higher level of health than before (antfragile, blue), (c) the ability to recover from damage (resilient, green), (d) the ability to withstand damage (robust, orange), and (e) breaking under stress (fragile, red).

The variety of ways initial success of military force can be undermined are manifest in examples ranging from ancient conflicts to modern wars. From the Punic wars to recent conflicts such as the Iraq War, as well as the classic examples of Napoleonic and German invasions of Russia in 1812 and 1939, many examples show that initial success in defeating enemy forces, or success in more limited measures such as occupying territory, does not necessarily translate into ultimate success in achieving desired goals. Even in the case of a successful defeat of a fragile enemy, the actual outcomes may not be the desired outcomes. A classic example is the Allies’ WWI victory and the subsequent political and economic sanctions imposed on Germany. The sanctions are generally considered to have contributed to the conditions that resulted in WWII.

Learning and adaptation enable antifragility, violating traditional strategic assumptions.

The history of military encounters, as well as complex systems theoretical insights, suggest that traditional military strategy is too limited an approach to reliably achieve desired goals.

A successful strategy is therefore one that recognizes not only the immediate objective, but also the existence of other goals that constrain methods or enable multiple goals to be achieved.

Today, a key challenge is identifying how to transition to new forms of cooperation in the face of a diversity of local values and objectives.

An initial defeat may trigger mobilization of the larger society, propelling an adversary’s military force to subsequent victory. This suggests that military strategy must consider an evaluation of societal strength and weakness, rather than just the existing military forces, as a longer term indicator of success.

Reliance on forecasts is likely to result in misleading information and misplaced confidence. Effectiveness of pre-specified sequential strategies is limited because they rely on anticipation of intermediate outcomes. Chaotic unpredictability is embodied in the adage “no plan survives first contact with the enemy.”

Fragility is characterized by deterioration under stress.

The damage from 10 shocks is generally much less than the damage from a single shock with 10-fold force.

Robustness and resilience characterize systems that tolerate stress.

Resilience and robustness do not imply gains in strength, as does antifragility.

Anticipation involves sensitivity to signals and the ability to interpret them as indicators of potential future harm (or benefit). Anticipation also requires dynamic response that prevents harm or takes advantage of opportunities. The difference between robustness and anticipatory response can be seen in a biological context in the generic response capabilities of plants and animals. While plants survive when parts of them are eaten by animals, animals often survive by fighting or fleeing. This capability reffects sensor-action coupling through an intermediate processing system in response to information in the signal about future events. Since the signal for the impending harm has a smaller impact than the harm itself, this is the origin of the term “sensitivity” in the ability to achieve anticipatory response. Such sensitivity enhances complex systems capabilities across a variety of contexts.

The foundations of antifragility as a basis for military strategy are evolution, learning, and adaptation. An antifragile system must be dynamic, and can, at the level of human institutions, be intentionally constructed exploiting mechanisms that give rise to antifragility. Evolution is a repeated process of selection and reproduction with variation: Varieties that outperform their predecessors become the basis for the next round of variation, competition and selection. Antifragility emerges in a system when its components are selected and replicated according to their contribution to system effectiveness. As a result, the entire system is strengthened when shocks lead to selection of effective components.

In the context of human society, variation often arises from creativity and innovation in ideas or behaviors. Selection and replication occur when successes and failures lead others to make changes in their behavior by adopting the innovations in ideas and behaviors. Stresses cause selection pressure that eliminates less successful variants of behavior. When the adoption of more successful behaviors occurs, the entire population can better withstand similar stresses and thus the system as a whole is strengthened. Evolution contributes to antifragility at the collective or organizational level, but individual components remain fragile due to the process of selection.

Human adaptation takes many forms, some of which occur without conscious action. An example is human muscle growth and increase in cardiovascular capacity.

The relevance of learning and adaptation to antifragility makes clear that antifragility is already central to military doctrine in training at an individual and tactical level.

A traditional analysis of military capabilities focuses on mobilized forces and does not account for the unmobilized forces that may be mobilized in response to an attack. It is apparent from our discussion that strategic analysis should include the potential unmobilized forces in conjunction with values that would lead to their mobilization. A recognized failure of such analysis occurred in the invasion of Iraq, where stated expectations suggested that much of the populace would welcome an invasion that deposed Saddam Hussein. However, such a response did not occur.

One general organizational lesson from evolution is that to make an organization antifragile, components of the organization should have a diversity of behaviors rather than uniformity through standardization. This diversity enables the recognition of variants that are more or less successful in response to a stress. The better performing variants can be replicated to improve the response to future stresses. In order for this process to take place, measures of success and failure must be incorporated in feedback processes that promote learning across the organizational units. Learning facilitates adaptation that is important both tactically and strategically. The incorporation of intentional diversity into unit behavior goes against the military tendency toward homogenization and “harmonization.” Such homogenization is consistent with and motivated by considerations of large scale efficiency but limits complexity and adaptability. Homogenization is also appropriate when there is predictability about what actions are needed. Homogeneity is ineffiective when there is a lack of predictability about the types of stress to be faced. Complexity in the conditions and needed response to them should be met by increasing variety rather than homogeneity.

As a consequence, there are compelling reasons to compress the timeframe and reduce the cost of learning; in other words, “fail early, often, and small.”

Strategists should consider military conflict one process in an on-going relationship between groups, with the indirect effects on the political, social, and economic aspects of that relationship as, or more important than, the direct physical effects on the enemy forces.